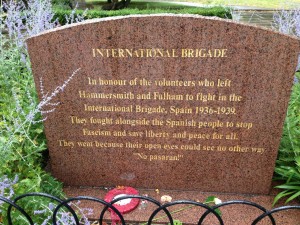

His socialism was shaped by the political polarisations of Europe in the thirties. Injustice and humbug were the enemies. It was rekindled half a century later during the Thatcher decade, when I got to know him through the Labour Party and my union’s support of the International Brigade Memorial Appeal, of which he was the secretary and which raised the handsome sculpture now standing in London’s Jubilee Gardens.

He was never a member of socialism’s dour tendency. His poems poking fun at Thatcher-ite values appeared regularly in Tribune during the eighties. Tribune also received the proceeds of one of his inspired brainchilds: the “Do Not” plastic card to be carried in wallets to instruct hospital staff not to allow Mrs Thatcher to visit the bearer in the event of being injured in a major disaster. Jimmy Jump’s fascination with Spanish in part came about as an accident of birth. Merseyside’s maritime connections with the Iberian peninsula and South America meant that Wallasey Grammar School, exceptionally for the time, taught its pupils Spanish.

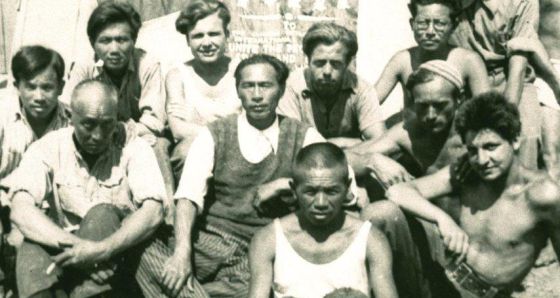

So uncommon were Spanish speakers then that, though only barely proficient to begin with, he served as an interpreter as well as a machine gunner in the British Battalion of the International Brigade.

After the second world war he gave up journalism, trained as a teacher and settled in Kent with his Spanish wife, Cayetana, eventually becoming a lecturer at the Medway College of Technology. He had 14 books on Spain and its language published during this period. It always made him chuckle that he had persuaded a leading textbooks publisher to accept an O-level reader on the 1938 Battle of the Ebro, in which he had fought and been mentioned in despatches for bravery.

“It was like giving birth to an elephant,” he said when the Penguin dictionary which had been commissioned 22 years previously appeared in print. This year also saw the publication of his third anthology of poems, With Machine Gun and Pen. Eric Heffer, in his introduction, said they moved him to tears.

Jimmy Jump leaves many friends and admirers in the British Isles and Spain. They will remember him as much for his warmth, humour and childlike sensibilities — so evident in much of his verse — as for his more public achievements.

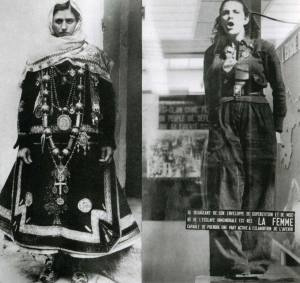

When speaking of the Spanish Civil War he preferred to dwell on the lighter, even farcical, moments, one of which still makes me laugh. Having been briefed at a secret address in Paris on the travel arrangements to the Spanish border, he was given a plain brown paper parcel with food for the journey — and strict instructions not to speak to anyone. “Imagine my surprise,” he would say, “when, on arriving at the Gare de Lyon, I saw more than a hundred young men milling about on the platform, each carrying an identical brown paper bag. This was no spy film; it was more like Laurel and Hardy.”

His son and daughter, who were with him when he died, report that he managed a broad smile when told that it was the first day for over 11 years that Mrs Thatcher was not prime minister.

Srenda Dean

James Robert Jump born August 24,1916; died November 29, 1990