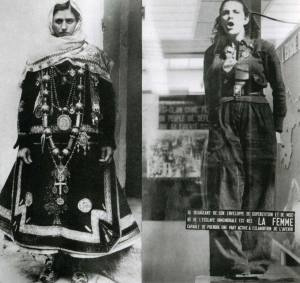

Striking photomural by Josep Renau, exhibited at the Spanish Pavilion of the 1937 Paris World’s Fair (as was Guernica), contrasting a woman from Salamanca in bridal dress and a militiawoman from Barcelona – in trousers as she strides confidently forward.. The legend on the glass under the militiawoman confirms this message: “The New Woman of Spain has rid herself of the superstitions and misery of her past enslavement and is reborn and capable of taking part in the celebration of the future”

“Superimposed on a glass wall, and standing side by side, are life-sized photos of two Spanish women. One woman is dressed in a traditional, elaborately constructed, and richly decorated wedding dress. The other woman, a Republican militiawoman, is wearing an open-collared shirt and trousers. The woman wearing the traditional dress appears weighted down by its voluminous multi-layered skirt and long sleeves. Her arms hang down limply by her side, her mouth is tightly closed, and she stares straight ahead. In comparison, the fabric of the trousers and shirt of the militiawoman is lightweight enough to appear to be moving as she strides confidently forward. Her arms convey strength and movement, as does her left shoulder, which seems to more toward the viewer. The woman’s mouth is open and she appears to be issuing some sort of command. Her eyes are piercing and intent. Her head is uncovered and her hair is pulled off her face. Unlike the bride in the other photograph, this woman appears to be walking out of the display straight towards the visitor. The only adornment on her clothing is a leather strap across her shoulder–possibly a gun holster–investing her with an aggressive and militaristic persona. ”

Explaining the intended message of Renau’s photomural,Jordana Mendelson writes:

…Renau contrasted the Arxiu Mas image of traditional culture with the forward stride of a young militia woman. The photomural

used the visual comparison to reinforce a message about the liberation of women under the Republic: shedding her age-old

traditional dress, the new woman of the revolution would find freedom in her fight against fascism.The legend on the glass under the militiawoman confirms this message: “The New Woman of Spain has rid herself of the superstitions and misery of her past enslavement and is reborn and capable of taking part in the celebration of the future” (Graham 112 n.7).

For visitors to the 1937 World’s Fair, the trousers on the miliciana would have been the most obvious sign of Spanish women’s new emancipation and alignment with aggressive political action. As Nash explains … for [Spanish] women the wearing of trousers or monos [blue

overalls] acquired an even deeper significance, as women had never before adopted such masculine attire. So for women, donning the

militia/revolutionary uniform not only meant an exterior identification with the process of social change but also a

challenge to traditional female attire and appearance.